Based on a research presentation, ”The Colorado River Compact” by Max Fefer offered February 28th 2018

Introduction: The Case for Examining the History of the Colorado River Compact

The Colorado River is a major supplier of water for cities and agriculture, and therefore a primary driver of economic activity, in the American West. Recent droughts affecting the West Coast of the United States and Mexico combined with increased for water have led to water budget deficits on the Colorado River. In order to understand which policy proposals might address the increasingly urgent issue of water shortage, it is important to consider both the present state and history of water allocation in the Colorado River Basin.

The Colorado River Compact: Present Day Governance on the Colorado

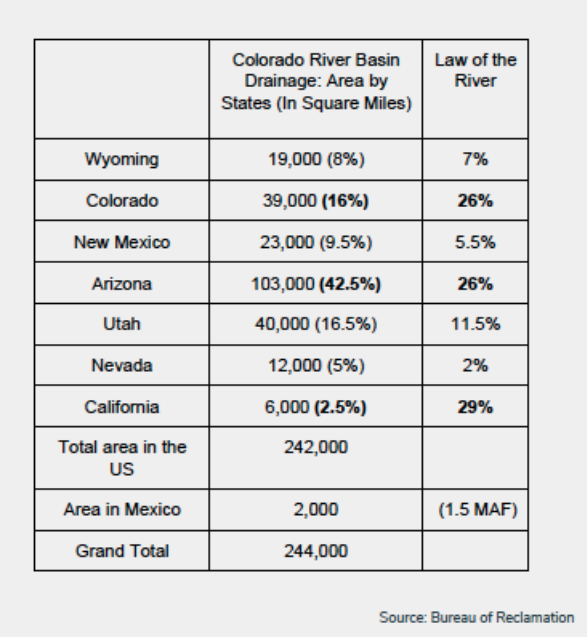

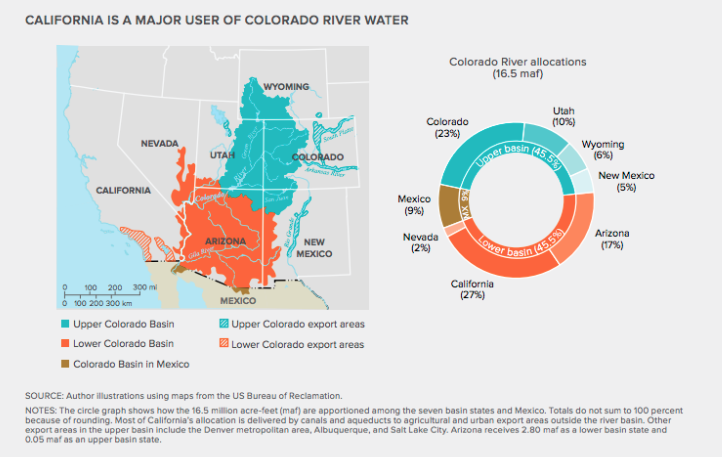

The Colorado River Compact, established in 1922, governs present day water allocation in the Colorado River Basin. This inter-state, international agreement awards 7.5 million acre feet (MAF) the Upper (comprised of Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado) and Lower Basins (comprised of Nevada, California, Arizona, and New Mexico). Currently, Law of the River provides an additional 1.5 MAF in allocation to Mexico. California holds the single largest share of any entity, drawing 27% of the total annual allocation. Though the Colorado River Compact was established in 1922, a wide variety of state, federal and international agreements and case law continue to shape and refine the access to water along the Colorado River.

The Law of the River – Collective Compacts, Laws, Regulations, and Court Decisions

While the Colorado River Compact is the most impactful agreement governing the Colorado River Basin’s water allocation, many other key laws, provisions, and agreements shape present-day water rights on the River. The 1928 Boulder Canyon Project, permitted construction of the Hoover Dam and assigned state specific allocation in the Lower Basin. The Mexican Water Treaty of 1944 established Mexico’s claim to 1.5 MAF on the Colorado River. The Upper Colorado River Basin Compact of 1948 assigned state-specific allocation in the Upper Basin. In a dispute lasting more than 60 years, Arizona v. California called the Compact into question and debated water allocation in the Lower Basin.

Today the Colorado River Compact and the assembly of policies and agreements, often called the Law of the River, combine to determine usage. Still, not all parties are entirely satisfied with the agreement. Some entities, like California, receive allocations that are disproportionally larger than the river basin drainage area within their borders. Other entities, like Arizona, receive allocations disproportionately smaller.

Negotiating the Compact: Who is up? Who is down? Who is not in the room?

Throughout the 1800s as the Imperial Valley and Los Angeles developed rapidly, states in the Upper Colorado Basin grew concerned about the ways in which related increases in agricultural and human water use in the Lower Basin would impact the basin as a whole. The League of the Southwest, formed in 1919 gathered basin stakeholders to discuss development and water usage. Two years later, Congress authorized the formation of the Colorado River Commission, then headed by Herbert Hoover, to begin initial drafts to divide water rights on the Colorado.

The Federal Bureau of Reclamation, an agency under the Department of Interior, served as arbiter between the water-rich Upper Basin and economically powerful Lower Basin. Notably excluded from consideration were Native Americans Nations and the nation of Mexico. Both of these parties exist, like the parties included in negotiation, within the Colorado Basin.

After 11 months of negotiation, agreement was reached. At the time 7.5 MAF were allocated for the Upper and Lower Basins with an additional 1 MAF for the Lower Colorado.

Informing Future Compacts: What can be learned from the Case of the Colorado River?

A powerful driver in the need for an agreement on the Colorado was the rapid development of the West. Southern California, unlike Arizona, had infrastructure in place to support rapid growth in the 1920s. Large allocations to this area, perhaps sped growth at the expense of other regions. The original promise of the compact was that proactive, collective decision-making with regard to allocation would ensure avoidance of litigation. However, the process failed to be inclusive resulting in a number of additional policies and therefore complex governance on the Colorado. Consensus building around water is challenging because of various competing interests regarding allocation, hydropower, urban development and water storage.

Entities in interested in learning from the case of the Colorado Compact might consider a cooperative sub-federalism approach to problem solving. This approach calls for national, state, and local governments to work together toward comprehensive policies.