Ecl290 class presentation: Jesse Jankowski

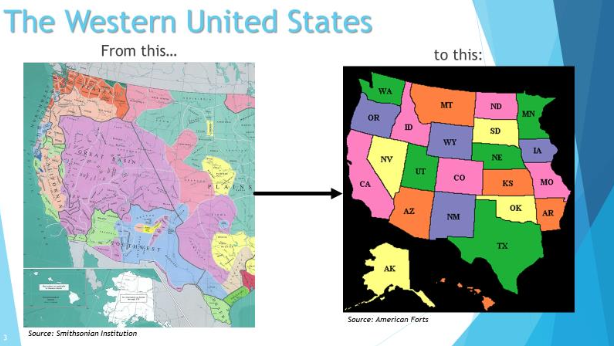

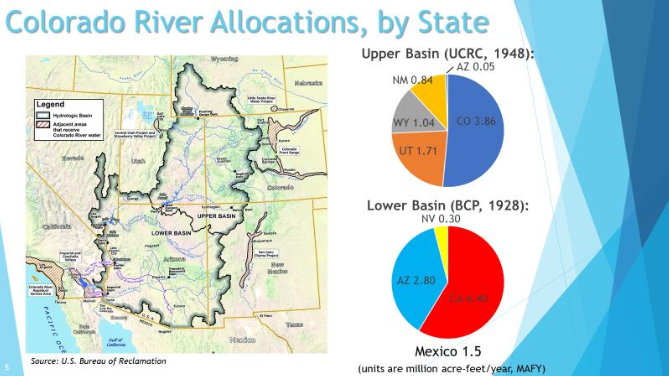

The Western United States went from being delineated by geographic features, like rivers and mountain ranges, to being further carved up by arbitrarily drawn political boundaries—state lines. To handle this change water, obviously a precious resource, was divided up by the states in a number of treaties. Specifically, the 7 states that make up the Colorado river basin catchment area signed the Colorado River Compact of 1922 (Bannister 1923). The compact governs water allocation for the parties involved in this inter-state agreement. This compact forms the foundation of the tome like collection of court rulings, appeals and contracts that govern the management of the Colorado River, colloquially known as the Law of the River (Lochhead 2000). As one might imagine, managing an abundant but dynamic resource like a river is both complicated and fraught. Creating a situation where all the stake holders feel heard, and are able to use the resources that they need is the goal.

On its 1,450 mile length, the Colorado river touches land allotments for 26 different Native American tribes. This is important not only for the human value the tribes have and the bond they share with the river. It is also important because tribes have a unique legal status generally and especially in terms of water rights.

Tribes have a direct trust relationship with the federal government. Put simply, this implies that the federal government has certain legally enforceable responsibilities to the tribes. The situation is analogous to a foster parent and child. They might be separate entities, i.e. different families, but there are certain things that a foster parent is required, by law, to provide for the child—food and water for example. A similar situation exists between the federal government and the Tribes where the federal government is required to facilitate the tribes access to resources.

Western water rights are governed by a doctrine known as prior appropriation (Tarlock 2000). The way it works is the first person to take water and use it for something, like farming, has claim to that amount of water in perpetuity. So called: ‘First in time first in right.’ Another way to think about this precedent is to imagine a pie. If you are the first person to find the pie your roommate baked and placed on the windowsill to cool. You take a slice of your found pie. In the doctrine of prior appropriation, you are guaranteed a slice of pie, as large as the historical slice whenever anyone makes a pie. Establishing this, historical water use, for an industrial farm is relatively trivial. Establishing it for a group of people going back to days of before recorded water usage is decidedly more difficult. In addition to this stitching together people’s water rights in a system with many stake holders is far from trivial. Adding to this difficulty, is the fact that there is a wildly different amount of water available each year as a result of things like rainfall and snow fall.

So there are really two options for how we can deal this situation complicated situation.

Option A) We can litigate our way through this process. The name for this legal wrangling is stream adjudication and it is both expensive, and time consuming. Furthermore, the courts have no funding power or authority and decisions reached through this process often result in ‘paper’ water rights which are not utilized.

Option B) would involve partnering with Tribes, Federal, and State agencies to settle and compromise toward effective resource utilization.

These two processes have very different potential outcomes for the stake holders. Litigation fosters the already well laid groundwork of distrust between the Tribes and the Federal Government. Compromise and settlement could work as a tool to, in a small way, build trust rather than sow discord. Compromise and settlement would also lead to more efficient use of Colorado water resources through funneling money toward development of existing water rights and better coordination of ancillary projects that would allow for delivery of water from new projects to smooth over shortages and utilize surplus resources.

Whatever is decided, the Tribes rights are not going away. Neither are the needs of state and local governments nor are the individual stake holder concerns in danger of disappearing. Doing nothing, in terms of managing how water compacts continue to be drawn up, is not a viable option. Only through reframing the government and the Tribes as allies and partners rather than adversaries will we be able to achieve a more equitable outcome.

Bannister, L. W. (1923). "Colorado River Compact." Cornell LQ 9: 388.

Lochhead, J. S. (2000). "An Upper Basin Perspective on California's Claims to Water from the Colorado

River Part I: The Law of the River." U. Denv. Water L. Rev. 4: 290.

Tarlock, A. D. (2000). "Prior appropriation: Rule, principle, or rhetoric." NDL Rev. 76: 881.