The Grand Canyon National Park is an awe-inspiring landscape – 18 miles at its widest point, over a mile deep, and a river that historically carried unfathomable amounts of sediment and rose hundreds of feet during catastrophic floods. Situated in the arid Colorado Plateau, this rugged and seemingly inhospitable environment was home to the Ancestral Pueblo Indians for thousands of years. On Wednesday, January 27, I listened to a presentation by UC Davis graduate student Madeline Gottlieb on natural resource use and environmental impacts in the Grand Canyon, including several current controversies that may impact the future of the National Park.

To the best of our knowledge, the first people to inhabit the land in and around the Grand Canyon were the Ancestral Puebloans (sometimes referred to as Anasazi’s, a name given to them by the Navajo tribe meaning “ancestors of our enemies”) approximately 4,000 years ago. They were a hunter-gatherer society known for their basket making. Common foods include pinion nuts and juniper berries, goosefoot, Indian ricegrass, yucca, and amaranth seeds. The modern day Hopi, descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans, are culturally distinguished when their society switched from hunting and gathering to agriculture and building large villages of interconnected adobe structures called “pueblos” around 750-900 AD. The Hopi learned to grow (and still grow) maize (corn), beans, and squash despite the harsh growing conditions. One interesting aspect of the Hopi society was the development of a salt mine on the canyon floor that was used as part of a pilgrimage to initiate males into adulthood.

Other tribes in the Grand Canyon Area include the Havasupai and Hualapai (ethnically one group that later split) arriving around 1200 AD and the Navajo arriving around 1400 AD. The Havasupai and Hualapai would move down into the canyon during the summer months to irrigate their crops and move up to the canyon rim to hunt game during the winter months. The Navajo were a nomadic hunter-gatherer society but later learned to grow crops from the Hopi. After the Spanish arrived in the mid-1500’s, bringing sheep, goats, and horses, the Navajo relied heavily on herding livestock. By the 1880’s, silversmithing and jewelry-making were an important part of Navajo society. Today, all four tribes place a heavy emphasis on tourism.

Anglo-Europeans arrived in the late 1820’s bringing along a huge demand for resources including heavy cattle grazing and logging resulting in an influx of invasive species and dramatically altering the ecosystem. By the early 1900’s, the ponderosa pine forests on the south rim of the canyon were almost completely exploited. Predatory animals like mountain lions, bobcats, wolves and coyotes were exterminated, causing the deer population to soar and consume all the available browse (a tale best told in Aldo Leopold’s essay “Thinking Like a Mountain”). Some protection to the Grand Canyon came in 1919 when Woodrow Wilson dedicated it as a National Park, though the impacts to the ecosystem were not over.

Perhaps the biggest affect on the Grand Canyon has been the construction of two large hydroelectric dams, Hoover Dam in 1936 and Glen Canyon Dam in 1963. These two dams, along with dozens of others in the headwaters of the Colorado River, have turned the warm sediment-laden river with seasonally variable flows into a steady cold trickle that rarely makes it to the ocean. Six of the eight species of fish that once thrived in the Grand Canyon exist only in the Colorado River basin and three of those species have been eliminated from the Park due to the dams. The sediment that once deposited sandbars and created a variety of habitats has dwindled as it is trapped behind the dams.

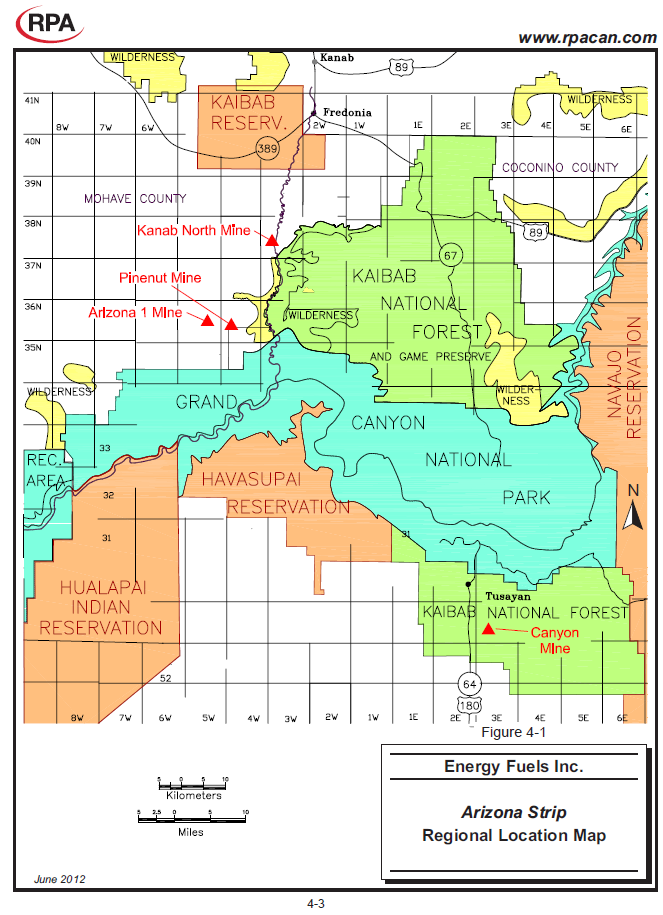

Aside from the dams, one of the biggest controversies for the future of the Grand Canyon is the re-opening of Canyon Mine, a uranium mine operated by Energy Fuels, Inc., six miles from the rim of the canyon. In 2012, then Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar issued a 20-year ban on new mining claims and mine development on existing claims without valid permits. On April 7, 2015 the U.S. District Court Judge Campbell found that the mining company had valid mineral rights and met the requirements of the National Environmental Protection Act prior to the declaration of the mining ban and therefore was not bound to the ban. On April 14, 2015 the Havasupai Tribe, Sierra Club, Grand Canyon Trust, and the Center for Biological Diversity filed an appeal and the issue remains unresolved. In addition, there is a petition created by Environment America to urge President Obama to create a Grand Canyon Watershed National Monument in Arizona to protect the watershed from uranium mining. Look for more information on this topic as the three-judge panel in the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reviews the case.