Humpback Chub, a fish species that has been on the endangered list since 1967, are not the only ones complaining about the temperature of water below Glen Canyon dam in the Grand Canyon, though they are perhaps the biggest victim of changes in temperature regimes since the introduction of the dam. Rafters used to enjoy temperatures up to 80 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer months and now, regardless of the season, need to dress warmly for the 44-53 degree water that now flows through the river. In fact, the only apparent beneficiary of the cold water are Salmonid fish species who like to spawn in 50-60 degree water, who have found their Goldilocks medium in their non-native Colorado River; “this water is just right.”

Before the dam was finished in 1966 the Colorado River went through a range of temperatures seasonally, oscillating between 32 and 80 degrees. Rivers are much better at responding to radiation from the sun than large water bodies like lakes and reservoirs. As they receive energy from this radiation the top layers of the water begin to warm, then this warm water is churned up and mixed with cold water at the bottom of the river during the regular rapids present throughout the Grand Canyon. This allows the full column of water to equilibrate with surface temperatures. A lake or reservoir, like Lake Powell above Glen Canyon dam, insulates the lower water layers from the sun’s energy, so only the top section of water experiences warming near to surface temperatures. The combination of mixing and having a higher ratio of surface area to volume allows the Colorado River to warm significantly faster than Lake Powell.

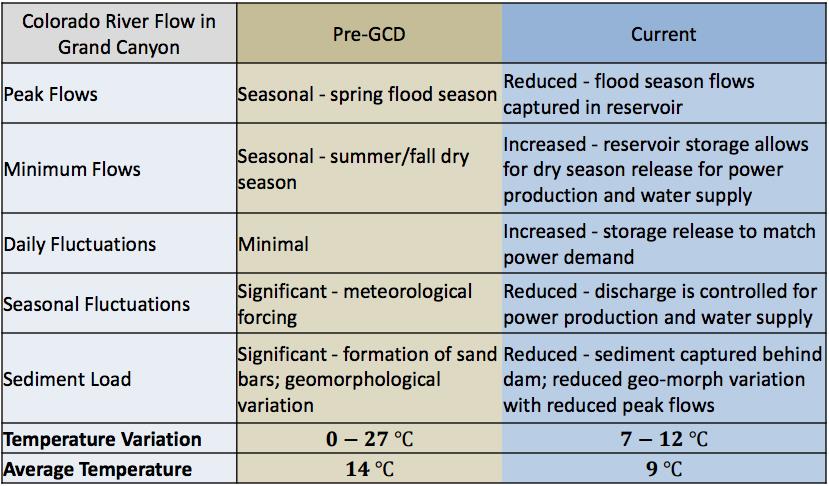

The Glen Canyon dam had an impact on many parts of the Colorado River including peak flows (reduced), minimum flows (increased), daily fluctuations (increased to control for power and water supply), seasonal fluctuations (reduced), sediment load (reduced, sediment is captured behind the dam), and temperature variation (Table 1). While all of these changes have had an ecological impact, perhaps the most significant for the native Humpack Chub was the change in the temperature regime. Now the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon is fed by releases from the bottom of Lake Powell through Glen Canyon dam. The water in Lake Powell is really cold, 44-53 degrees, almost all the time, regardless of the season.

The Humpback Chub is endemic to this region and spawns in 65-70 degree water. This means that since the dam has gone in no baby Chubs are born in the Colorado River. Instead the only large area in the region suitable for spawning is in the Little Colorado River, whose flow is, on average, 367 cubic feet per second (cfs). This is only 1.7% of the average flow in the Colorado River, 22,000 cfs. If losing the vast majority of their spawning sites weren’t enough, the temperature change has introduced another barrier to the Chub. Salmonid fish species have thrived in the cold and sediment-free dam release waters. These non-native fish were introduced in the early 20th century and are a major predator of the juvenile Chub, meaning it is harder than ever for the Chub to survive.

Like many environmentalists over the past 30 years, you may be wondering how we save this adorable face:

In fact there have been a few proposed mitigation options. One is the removal of the Glen Canyon Dam, though that has received little support as the impacts could be extreme and unanticipated, not to mention the loss of all the energy produced by the dam each year. The more tractable option is to build a temperature control device within the dam that would intake warm surface-level water, pass this to the tunnels with cold, deep water, then mix the two as water passes through power generating turbines. The final design for this option was finished in 2007, with an estimated cost of $25-80 million and was awaiting approval. Since a 2008 Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) report, however, there has been no mention of the temperature control device.

Derek Roberts, a student of UC Davis’ Ecology, Geology, and Geomorphology of the Colorado River course, reached out to the Manager of the Environmental Resources Division at BOR to find out the status of these plans that had seemingly dropped off the map. Ultimate the Fish and Wildlife Service did not support moving forward with the design, both because of the high cost and uncertain effects. There are fears that nonnative species, such as the Salmonids that prey on the Chub, may also benefit, ultimately leading to higher loss of the Chub. Finally, certain climate change forecasts have suggested that in coming decades temperature increases could have a large impact on the temperature of the water without adjusted dam release temperatures.

Perhaps in the future alternative mitigation options will be proposed, but for now our friend the endangered Humpback Chub will continue to survive on the fringes of its native Colorado River in the Grand Canyon.